I am late to the Maria Kang debate. I guess I could say my excuse is I’ve had pneumonia; but, more accurately, it’s taken some time for this all to sink in and for me to get my bearings and cultivate what I want to say.

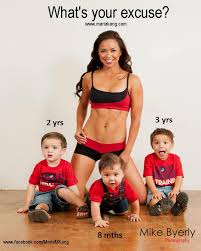

If you don’t know what it is (or was) all about, the accompanying photo here says most of what you need to know. Former beauty contestant now-business owner and fitness aficionado Maria Kang created quite a hubbub when she posted this photo of herself with her three young children. Criticism has run the gamut, of course: the way she’s dressed, the question she poses, the feelings she has incited in viewers.

If you don’t know what it is (or was) all about, the accompanying photo here says most of what you need to know. Former beauty contestant now-business owner and fitness aficionado Maria Kang created quite a hubbub when she posted this photo of herself with her three young children. Criticism has run the gamut, of course: the way she’s dressed, the question she poses, the feelings she has incited in viewers.

Her picture doesn’t provoke me nor does it inspire me. Instead it strikes me as yet another example of an individual shedding clothing, coupling their bare skin with a provocative statement, and waiting for his/her resulting five minutes of fame amidst the cacophony that is the internet. Nothing new to report.

What does give me pause is her question, What’s your excuse? which, since she posed it, I imagine I should answer: I wasn’t aware I needed one.

If you peruse Ms. Kang’s website, you will read details of loss in her young life that led her to dedicate herself to health and fitness. Like many of us, she was inspired by her early experiences and is trying to make the world a better place and save others the pain and suffering she knows all too well. It is a commendable if not familiar path.

She chose her line of work just as I’ve chosen mine and you’ve chosen yours. I became a teacher because it was my education that lifted me from my own tumultuous and unhealthy childhood. I write because I see human beings’ ability to communicate and be understood as our greatest gift. She is proud of her work as I am of mine.

The issue then becomes Ms. Kang’s question: What’s your excuse? I will stop short of analyzing the tone because, as we all know, as much as we aim to be clear in our communication, misunderstandings are rampant. It would be wrong for me to assume what she was thinking or intending when she wrote it.

What I will say is this: It is pretty easy to see, despite her or her supporters’ protestations, why people might view her query in a condescending or menacing way when it is coupled with that particular image. By putting the two side by side, she is saying, “What is your excuse for not looking like me?”

The blogosphere has been generous in responding to this iteration of her question. For me, it’s pretty straightforward: Ms. Kang’s life’s work is physical fitness. She spends hours helping others, I am sure, but also hours on herself. If I had to guess, she probably spends roughly the same number of hours helping others as I do with my students and as many hours on her own personal workout as I do slogging at the keyboard to improve my craft. She has her priorities, and I have mine—but priorities we both have.

What separates us is the fact that she put her accomplishment out there and asked the world why they haven’t accomplished the same. I have resisted the urge. Putting an image up of an “A” on a grammar test or a recently published article and asking the world why they aren’t doing the same makes zero sense—not to mention it wouldn’t get a whole lot of hits compared to a scantily clad young woman.

To expect the world to reach the same heights we reach in our particular fields sounds noble, but it’s not. It’s boasting–saying that what we do is superior to the work of others, telling people to stop doing the work of their hearts and minds and do what is important to us. Here reside elements of selfishness, misguidedness, and, ultimately, insecurity.

A well-known Spanish proverb says, “Tell me what you brag about, and I’ll tell you what you lack.” I’ll let the author of the proverb tell Ms. Kang –or the rest of us, for that matter—what we lack. I’m not qualified.

But maybe there’s a better idea. Perhaps we should all stop telling—or showing–each other what we lack. Maybe if instead of challenging one another to be like us, to do as we do, we look at and appreciate each other’s differences and celebrate one another’s accomplishments. Maybe then people’s insecurities and their resulting and often unfortunate choices would not take center stage.

We need this shift now more than ever.

What’s our excuse?